No Men Poodles or Milksops

THE FOOTBALL JUBILEE: HOW THE GAME STARTED

By OBSERVER

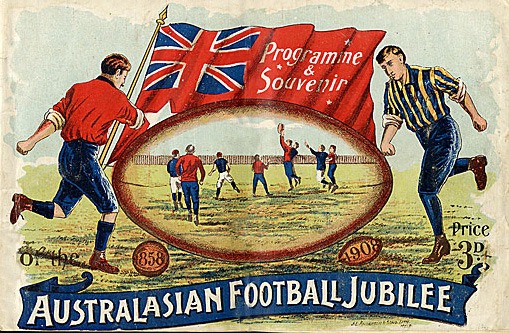

Australasian Football Jubilee Carnival 1858-1908 – Souvenir Programme

Exactly fifty years after Mr. Harrison and his cousin discussed the founding of a new game, the Rugby League of New South Wales suggests that a composite game might be agreed upon as the universal winter sport for Australia. It is not the first time the suggestion has been made. When, in 1884, Mr. Harrison went to England on a holiday tour with the Australian Eleven, he interviewed the authorities of both the Association and Rugby games, with the idea of arranging an exhibition match under Australian rules, and offered to devote three weeks to coaching the teams in the main points of the game. Mr. Alcock, then secretary of the Surrey County Cricket Club, was a leading official in Association football, and he had heard so much from English cricketers visiting Australia about our game that he offered the use of Kennington Oval for the match and agreed to find an Association team to play in it. The Rugby people were, however, less cordial. Their standpoint was

This game of ours is 150 years old. If one of us has to adopt the other’s rules the obligation is surely upon you-the younger people-to adopt our game.

It was not in one sense an unreasonable view and had Rugby been the only game played in England at the time the argument would have been unanswerable. But England had its rival games and, though Mr. Harrison’s suggestion appeared to be in some sense audacious, it at least offered a compromise between the two as a universal game, putting Australian interests on the matter quite upon one side.

HCA Harrison – father of the game

Later on, when returning to Australia, Mr. Harrison made an effort to impress New Zealanders with the merits of Australian rules. Joe Warbrick, the famous guide of the buried pink terraces, and other leading New Zealand players were impressed, but they all said the same thing.

See Mr. O’Neil. He is the father of football here, and whatever he suggests we are willing to do.

Mr. O’Neil was, however, a Rugby enthusiast, very courteous, but very firm in the belief that there was and could be no better game in the world than Rugby. Mr. O’Neil’s strongest objection was,

If we adopt your rules, it means that we give up all hope of ever playing matches with the old country. That prospect is too great a thing to sacrifice

This happened 25 years ago, and since then only two New Zealand teams have visited England, though the famous All Blacks established a record upon their tour which has certainly placed New Zealand football upon a very high pinnacle.

As this year is the jubilee of Australian football, it is also the jubilee year of the Melbourne club. South Yarra was the second club formed, Carlton and Albert Park (which finally became South Melbourne) were founded in 1864, East Melbourne in 1868, Carlton Imperial in 1869, and St. Kilda in 1873, while North Melbourne was indirectly represented for a time in a team known as the Royal Park.

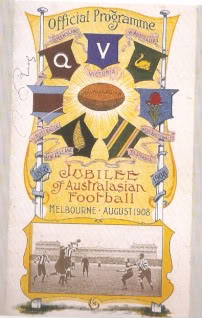

Australasian Football Jubilee Carnival 1908 – Program

The first regular club matches were played between Melbourne and South Yarra, which had its ground at the back of the Presbyterian Church, in Fawkner park. Amongst the notable men of the South Yarra team at the period were the late Judge Fellowes, George O’Mullane (a first-rate cricketer), and Mr. R. Murray Smith, of whom Mr. Harrison, in a chat about these early days, says

“He was one of the fairest, as well as one of the pluckiest, of players. He took his spills with a smile and never lost his temper. I always held him up as a model of what a manly and good tempered athlete ought to be. George O’Mullane, though a strong, running player, a fine drop kick, and a man who used his strength when there was need of it, had also a fine temper and it was a pleasure to meet him on the field – even when the meeting was shoulder to shoulder, and you happened to get a trifle the worst of it.”

The footballer of those early days led the strenuous life, whether he wished for it or not. As Mr. Harrison himself remarked, after a game between Melbourne and Albert Park, where Melbourne were charged with playing roughly, it was not a game for “men poodles and milksops.” The Fourteenth Regiment just returned from pah-storming in the Maori War, played it not strictly to rule perhaps – if there was any rule worth mention – but with a whole-hearted ardour that covered all technical deficiencies. Captain Noyes, who led the Fourteenth in these more serious phases of foreign service, was a fast, plucky, dashing player, whose plan of action was to run with the ball, and when he could run no further to lie down, with the ball under him, while the Fourteenth rallied to their commander, as the chivalry of Scotland gathered round then fallen King upon Flodden field- “grimly dying, still unconquered, with their faces to the foe.” The challenge of the gallant Fourteenth, “Wan o’ yoz touch him if you dar’,” was conveyed in word and look, the light of battle blazed in then Irish eyes, and the consequence generally was that Captain Noyes got his spell and made a fresh start.

On one occasion Mr. Harrison, after being kicked about seven times on the shins by his opponent – he carries his honourable scars to this day – protested, with as much mildness as the captain of the Melbourne could command under such circumstances, that it was not quite according to the rules.

Blasht yer rules! was the prompt retort; we’re playin’ Irish rules.

If there was any peculiarity in the Irish rules of football as interpreted by the Fourteenth Regiment, it was extreme liberty of action – maintenance of the fine principle that a man’s free impulses should not be unduly curbed by artificial restrictions. After one defeat the Fourteenth said, “Wait till Lieutenant Blank comes, an’ we’ll give yiz fits.” Lieutenant Blank arrived in due course. He was not an alarming figure, but he wore a belt, upon which was blazoned the grim inscription, “Neck or Nothing.” It was in one sense neck, and in another nothing, for within 10 seconds of the start the gallant lieutenant encountered Mr. Charles Forrester, the staid and gentlemanly golfer of today, and was carried off the field a limp and useless casualty. There was a good deal of “Hit her a lick, Mick,” in the footballing methods of the Fourteenth Regiment, and, fortunately for the British army, they played in days when an umpire was not considered essential, except at the goals. If there was any gross breach of etiquette, verging very nearly upon manslaughter, a free kick was sometimes claimed, and it was left to the chivalry of the opposing captain to say whether the claim was justified. In this way nice points were sometimes presented. The portly captain of the South Yarra team, who could punt-kick as far and as high as Caine, of Carlton, once stopped the match and claimed a free kick, on the ground that an opponent had contemptuously referred to him as “a lump of blubber.” It was a difficult point, but the sports of the period agreed that the provocation was sufficient to warrant a free kick of some sort without being so precise as to say where the kick should be delivered.

To those who know Australian football today it seems almost incomprehensible that for many years there was no field umpire. There were certain unwritten rules, and if any of these were badly broken the captain of the suffering side had the right to claim a free kick. That meant stopping the game. It also meant, in some cases, a long argument as to the merits of the case, so that only in extreme cases was the free kick claimed. The first formal code of rules was adopted at a meeting of delegates from the leading clubs, held at the Freemasons’ Hotel in 1866. Mr. Harrison prepared the code, which was adopted without alteration and in many instances the wording of a rule has been retained. Even then there was no provision in the game for a central umpire, the nearest of the goal umpires being called upon, in case of dispute, to settle the difference.

George Coulthard – Carlton

At a comparatively late period in the history of Australian football there was every prospect of a compromise being arranged between New South Wales and Victoria. The Waratah club, of Sydney, came down to Melbourne and arranged to play two games against Carlton under Australian and Rugby rules. Each club had apparently reasoned the matter out in the same way. Each was certain to win under its own rules and so gave a great deal of attention to the rival game in the hope of effecting a surprise. The result was that Carlton rather astonished their rivals by their proficiency in Rugby, and were in turn, surprised to find the Waratah playing a rattling good game under Australian rules. Soon afterwards George Coulthard, one of the finest players who ever wore Carlton colours was taken to Sydney to coach their footballers in the Australian game, but a little misadventure in Port Jackson brought the engagement to a sudden close.

Coulthard was fishing with some friends one day from a boat in the harbour, when he suddenly disappeared over the stern. His coat, trailing in the water, had attracted a shark, which took a mouthful of it. Fortunately, the coat gave way, and Coulthard was rescued, but after that experience he was never happy in Sydney, and soon returned to Melbourne.

At that time all the conditions were favourable for a compromise, and the founding of a universal Australian game. Mr. Phil Sheridan, a trustee of the Sydney Cricket ground, tried hard to induce two of the leading Victorian clubs to visit Sydney and play a series of exhibition matches, so that Sydney people might be able to see the Australian game at its best. He failed in the effort, but always maintained that had his scheme been adopted, Australian football would have displaced Rugby in Sydney.

The evolution of Australian football as a sport has gone on slowly and steadily for 50 years. No sweeping alterations in the rules were ever made, but as defects became flagrant they were remedied. At one time the side scoring the first two goals won the match and sometimes after three hours’ solid play it was necessary to continue the game on the following Saturday, so that the necessary two goals might be scored. The absurdity of this plan became apparent on one occasion, when Geelong sent up a team to play Melbourne. There was a strong wind blowing, and at that time the custom was to change ends whenever a goal was scored. The game was won in less than half an hour and a scratch match had to be arranged to fill up time. Even when football had become a popular sport in Victoria, it was noticeable that very few goals were scored. Melbourne on one occasion went through a season unbeaten and had only one goal kicked against them. That was scored by Geelong, owing to the mistake of the Melbourne goal-keeper, Gourlay, who ran out to meet a ball which bounced over his head. In that triumphant season Melbourne scored only 17 goals – a record now frequently beaten in a single match. The low scoring in these old days was, in Mr. Harrison’s opinion, wholly due to the greater liberty of action given by the rules. Pushing behind was allowed and that had more to do with spoiling the scoring chances than anything else.

It was a long time before the footballers were allowed to play upon the cricket grounds, the popular belief being that football would ruin the turf for cricket. Melbourne played at the back of the M.C.C. grandstand, on a rather rough tract, known as the gravel pits. They were not at first allowed to enclose a space and the consequence was that excited crowds so encroached upon the ground that its width was reduced to not more than 25 yards. On one occasion, when Melbourne and Carlton were playing a match, some “under and over” artists and three-card manipulators set up their stands on the playing ground, and invited the populace to pick the correct card. On being asked to move off, they pointed out that the park was public property, and they had the same right to it as the footballers. The plea was legally good, so other means had to be adopted. A conference of the players was held, and, Harrison said,

They are quite right. This is a public park; everyone can do as he pleases, so when I give the signal knock off play and follow me.

A few minutes later a wild whirl of footballers burst upon the confidence men, tables were sent flying, their owners turned head over heels by a purely accidental charge, and the whole difficulty was settled in one short, strenuous act.

The Melbourne Football Club asked for permission to enclose the ground, and offered to spend £600 in laying down turf, but the proposal was strongly opposed by the late Mr. FitzGibbon, then town clerk of Melbourne, who, like the footballers, had a masterly way of doing things. While they were still agitating for the use of the gravel patch, it was suddenly planted with the trees which now adorn it, and the footballers, were soon afterwards granted the privilege they had long sought of playing their games upon the cricket ground. The first match played inside satisfied the M.C.C. that footballers were worth considering, for £500 was taken at the gates, and before an argument so convincing all opposition to the use of the cricket-grounds in winter vanished. Indeed, anyone who takes the trouble to make a comparison between the balance-sheets of the Melbourne Cricket ground then and now will see that in the following season the M.C.C. had a remarkable increase in its members’ list, and took its first great step towards attaining the magnificent position which it now occupies.

Club colours were originally displayed in a cap only, but a special kind of tight-fitting, short-laced jacket close to the body was afterwards worn. In one respect it was a gain, and in others a loss. For example, W. Freeman, a player whom the Fourteenth used to call “that infernal eel.” had a trick of squirming his way through a crush that was rather destructive to shirts. When one was torn from his back he went to the pavilion and got another – generally the first that came handy. In one match, Harrison laughingly remarked that Freeman had gone in for his fifth shirt, but laughed less when he realised that Freeman was wearing his (Harrison’s) shirt. I was a very little lad when H. C. A. Harrison, T. S. Marshall, and a dozen or more other vigorous young athletes (amongst whom figured, as I have been told, the lamented Mr. T. W. Wills, afterwards famous in the cricket world), met by arrangement in the Richmond paddock one winter afternoon just half a century ago, and got the ball a-rolling. It was, however, very few years later when I grew old enough to appreciate pleasure of participating in the manly and health and strength giving sport, and old enough to note and to admire the men who played the game. Concerning the illustrious H.C.A. himself, and his prowess in the field, much might be said, and all of it commendatory. He was the mightiest warrior of his day.

When he headed a charge, his pace, his weight, his pluck, and his power seemed irresistible. I have seen him in the early popularity of the game, leading old Melbourne against old Carlton, on the historic convincing ground outside the M.C.C. reserve, and I have observed, times out of number, the fire, the forcefulness, and the tact with which he has repelled the fiercest onslaughts on his citadel. On these occasions his flashing eye, as much as his fine physique, awed and overwhelmed his adversaries. His followers worshipped him, and his opponents in the field learned to appreciate, not alone his fine physical gifts, but his genial qualities of mind as well, and, above all, his absolutely stainless sportsmanship. May the coming carnival afford him all the pleasure his unequalled service to the game has deserved and may he be spared many more years to watch and help its further advancement.

Those early days furnished heroes galore to help the sport along and the rough paddock at Richmond was not its only home. The start was made at the spot I have indicated, but even in the same year football was played with spirit and greatly enjoyed at Emerald Hill by “Mat” Ryan, who is still an ardent well wisher to the game, and a regular attendant at its matches. Last week I met him with W. W. Gaggin at East Melbourne, and both grew eloquent in praise of the football that was being played by Seward for University. “W.W.” had much to say, too, concerning football in the old, old days, when South Yarra won the cup from Melbourne; for they fought for something more than love even when H.C.A was young. Gaggin himself played for several years, and made a reputation that he subsequently enhanced in the gentler field of cricket. From him I learned that Morell was the most famous footballer South Yarra owned, notwithstanding that W. J. Greig, Dutton Budd, and his brother H.H. were clinkers in the southern team. And speaking of Harrison, my friend W.W. told me he once saw James Horan, on elder brother of Tom’s, effectually stop a dash of the great master by ducking as the latter spring at him with the ball. This must have been the earliest case of “rabbiting” in the history of the sport. “Mat “ Ryan tells me he captained Albert park for a year, and was succeeded by the Rev. A. Blown, who is still fond of looking at the game.

Migratory players have apparently been a trouble from the first, for I read, amongst the rules of the cup competition, already mentioned,

that no player shall take the field for more than two clubs during the season

Two would seem, in the light of recent developments, rather a liberal allowance.

The files of “The Australasian” become a bit perplexing when one is trying to fix upon the club to which an old celebrity belonged. They were nearer to Magna Carta in those days and permitted much more individual liberty than obtains under the present regime.

Mr. Harrison played on in the seventies, when he had for association many splendid fellows, including F. H. Bruford, now commissioner of audit ; “Billy” Freeman, a champion sprinter; J. Horan, who also played for Carlton, and “Larry” Bell, a player of magnificent proportions. Later on Melbourne was led by Lamrock, and after by “Bob” Sillett ; and T. Horan, subsequently famous in international cricket, and now “Felix” in more than one sense amongst cricket writers, “Jack” Bennie, who ran terrible risks, inasmuch as he played in spectacles; “Toppy” Longden, the cleverest of dodgers, and Angus Cumming, a bright little goal-getter, were con-spicuous members.

Melbourne’s strength was always fully tested about this period, and for decades after, when they faced Carlton, whose early honour roll includes names that are by no means yet forgotten. Donovan, a champion in his day, Harry Guy, than whom a neater or faster runner with the ball the game has scarce produced; W. Lacey the follower who had no peer, when “Sam” Wallace, the mighty was there to shield him; “Billy” Dedman, who could kick goals that would amaze a modem spectator; “Lanty” O’Brien, who did nothing but punt long before punting became fashionable ; and Alf McMichael, a man full of football and full of grit, who followed till he dropped in his tracks. The last named settled down in Adelaide for a while, and with Joe Traynor a fine player from Hotham, “Topsey” Waldron from Carlton, Harry Thurgurland, from Hotham; and J. Bushby from Ballarat, gave the game fresh impetus in the neighbouring capital. Harry Nudd was Carlton’s finest drop-kick in the days I write of; and George Browning rivalled him a few years later there was Billy Newing, too, a rattling little forward, and George Smith, who never said “die” is a follower.

The last named his a very worthy successor today in his son, D. Smith of Essendon. George Coulthard looms large in the football records of the eighties, when he was for years the best all-round player of Carlton. He could not be misplaced. His clever handling, his pace, his expertness in dodging, his sureness in the air and his masterful kicking were items that proved invaluable to his team. He was the brightest star in a galaxy, such as does not, even today, shed its effulgent beams on Carlton.

Take Jack Baker, for example. Where is the present dark blue warrior that can compare with him in his prime? And he was in his prime when he played with Coulthard. A graceful, breezy player, who carried the ball along with a rhythm that moved like music. How smoothly he glided past opponents, and how surely did he pick his man and kick to him? Jack was the best player that ever came away from Geelong, where, as a junior, he played with Charley Brownlow, the Geelong club’s capable and popular secretary and J. J. Trait, in whom during many later years the game possessed admittedly the best umpire that ever entered the field. The “Prince of Umpires” was the title earned by, and universally accorded to him. He was the only umpire who made it a rule to refrain from giving a free kick when giving it meant a disadvantage to the injured side, and he was the one umpire who, after a match, could tell you how it was played, who played well, and all about it. Jack Trail had what no umpire before or since his day has had – a perfect genius for the position. Coulthard had to compete for championship against Baker, against Harry Wilson, a player of Baker’s stamp exactly, and one who in ’81 was at his top. He had also as friendly rivals and comrades George Cook, W. Goer (who, with Coulthard, helped to plant the game in Sydney), Watling, C. and A. Coulson, Loriame, and Strickland (afterwards captain and chief adviser of Collingwood), who were infants when he took to nurturing and developing them.

Peter Burns – South Melbourne

Ballarat has done its share in building up the game of football, as it has done much more than its share in raising the financial status of the country. It has trained and sent down to the metropolis great numbers of players, who have played leading parts in securing for the game the popularity and patronage that are to day its proudest boast. Probably no one will question the statement that of all the men that have come from Ballarat Peter Burns has been by far the best. His years of masterful service at South Melbourne, where he was always head and shoulders over his associates, made him the idol of the Hill; nor did he forfeit the affection, admiration, or respect of his Southern associates of the district when business transplanted him to Geelong, to the great job and gain of the residents and players of that nursery for footballers. Ballarat furnished South Melbourne with other cracks besides Burns. D. M’Kay, a gifted all-round performer, and Harry Purdy, who was one of the best for years, likewise hailed from the golden city. South had a great side when these were in their zenith along with Windley (who has hardly yet stopped playing), poor M. Minchin, who practically died in harness; Jimmy Young, “the diddler” Elms, the best skipper South has ever known; Latchford, the expert goal-getter, who, it was said, could, from his doorstep in Clarendon street, drop-kick a ball straight into the glass top of the lamp across the way. There probably never was a “downier” or more skilful artist with the ball than Hannaysee, who, with another talented player, came to South about this time from Port Melbourne. There was P. Harper, too, and there were several others nearly as good who helped to make South Melbourne invincible.

Sam Bloomfield captained Carlton, and was the old club’s sturdiest ruck man for quite a time. He was a sportsman in the truest sense. No one ever knew him to do a mean act on or off the field, and his comrades placed thorough reliance on his judgment and discretion in emergencies. With him was associated George Robertson, a player blessed with magnificent physical development, remarkable activity for a burly man, and limitless staying power. It was during George’s connection with the club that it had to contend against disadvantages in the matter of a playing ground. George was, and I fancy, still is, a fine judge of a player, but he always had a prejudice against narrow chested men. He would not have a weed like Condon on his mind; and Condon, its everyone knows, was Collingwood’s and almost Victoria’s, champion for years. There was something of Julius Ceaser about the old Carlton skipper. He wanted fat (well-built) men about him.

James Wilson – Geelong

Geelong, in the early eighties, was on the crest, of the wave gaining premiership after premiership, and teaching the footballers of the metropolis the best lesson they have often been taught, namely, the true value of organisation. Such system as they developed had not previously been dreamt of in Melbourne, and the consequence was that for years they swept the board. They were the first club that really reduced football to a science and, though they went down badly in 1889, and have never fairly recovered since, they are still held in the highest esteem by the great bulk of the unattached public, who would be glad to see them once again at the top. James Wilson captained them through several of their prosperous years, and it was his superb all-round play, as much as his skill as dictator-general, that helped towards the continuance of then prosperity. He had with and under him a host of talent, including Steedman, Austin, Hall, and later Dave Higginbotham (who himself developed uncommon capacity for generalship), George Watson (between whom and Coulthard, of Carlton, I have witnessed many stubborn tussles); Hugh M’Lean, a great performer ; Phil. M’Shine, the finest marksman of his day, and Tom Parkin, than whom very few better followers have ever been seen.

Fitzroy, though its career has been a shot one computed with Melbourne and Carlton’s, can boast of having furnished its quota towards popularising football. First there was P. G. M’Shane who had previously played with Donald Macdonald out Essendon way, and who could run like a hare, and take the ball along with him, however fast he ran. Next came a contingent of lads who had learned to play at Maryborough, and by whom the whole aspect of things at Fitzroy was speedily improved. These very valuable newcomers were J. Worrall, Tom Banks and Con Hickey, who deserve well of Fitzroy for what they have done for it. Worrall, in his best day, had the art of roving perfected. Indeed, it is a moot point whether any champion, before or since his time, excelled him as in all-round player. He has given the game his chief attention during the winter months ever since he began at Fitzroy, and has acquired such judgment in the picking and coaching; of players that he has in a few years raised Carlton from the dust to the skies, and kept her there. Both Banks and Hickey were great players for years in the ranks and as leaders of Fitzroy and both are still invaluable members of the club’s executive and of the V.F.L. council. Mr. Hickey holds the very honourable position of president of the Australasian Football Council, a position which no man in or out of the Commonwealth is more fitted to occupy. Fitzroy has been fortunate in having the services of this illustrious trio and they have been further blessed with most skilful and successful members in Cleary, who migrated from Ballarat, Melling, Jim Grace, Rappiport, M’Speerin, Sam M’Michael, and Perry Trotter. The last named was for some seasons meteoric in his movements forward.

A. Thurgood – Essendon

Essendon’s period of greatest prosperity was that in which Thurgood was at his top, and won for years in succession the title to the championship. A champion he was most emphatically, for he could do what no other footballer ever did in Melbourne. I have seen him, when his side wanted three goals and had five minutes to play, leave his post up forward, go into the ruck, and carry the whole game on his back with such marvellous success that he has made his own opportunities, and practically, by his own unaided acts gained the goals necessary to win the match. This he did against Melbourne, in the presence of an immense crowd, every man and nearly every woman, amongst whom cheered him to the echo. There were more swallows than one to make glorious summer for Essendon in Thurgood’s day. Here are few names that should awaken delightful recollections. Alex Dick the best captain of his or any day, Gus, Keaney, Col. Campbell, Ned Officer, George Stuckey, Finlay, Forbes, and Barney Grecian. Prior to the days of Thurgood there were men of mark in red and black jerseys and of them I can recall without difficulty Ned Powell, W. Fleming, C. Pearson, Dave Aitken, F. and W. Hughes, S. Angwin, Jack Mouritz, W. Meader, and the original “Joker” Hall.

F. M’Ginis – Melbourne

To Tasmania belongs the honour of having produced the first artist amongst Melbournes cracks of fairly recent years. In Fred M’Ginis the club was blessed with a born footballer. I remember seeing him make his first appearance in the Melbourne team when he astonished and charmed me with his display. He simply dropped into his place as it he was made for it. He picked his men like one who had played With them for years and he was the personification of cool cleverness and resource.

And all that he showed himself on that first day, he remained up to the time when, unfortunately, his light went out literally, and he could no longer see to play. The pick of the men he played with, whilst in Melbourne, comprised H. Fry, Lewis, P. O’Dea, Christy, Moody, Moysey, and Dick Wardill.

In this rapid review of times past I have neglected to mention hundreds whose names were household words in their respective days and very sorry have I been to leave them out. Even at jubilee time footballers must not expect to have the paper entirely given over to chronicling their achievements.

Argus (Melbourne, Vic. : 1848 – 1957), Saturday 1 August 1908

19 August 1908

Today will see the commencement of the carnival arranged in Melbourne to celebrate the fiftieth anniversary of what is known as the Australian game of football. The event is being signalised in a unique but very appropriate way, teams representing all six states of the Commonwealth and also New Zealand having been sent to Melbourne to participate in a tournament for the honour of the championship of Australasia.

The ceremony was notable for the performance of “war cries” by both the New Zealand and Queensland teams.

The Maori war cry, given with great zest by the New Zealand team, and equally stirring was the aboriginal battle cry of the Queenslanders.

The second match, played immediately after the opening ceremony, was nowhere near as exciting: Tasmania beat Queensland by 140 points.

In competition, the teams’ uniforms were:

- New South Wales: Royal blue with a red waratah on breast; white knickers; royal blue hose.

- New Zealand: All black with gold fern leaf; black knickers; black hose,

- Queensland: Dark maroon with white ‘Q’ monogram; white knickers; maroon hose with white tops.

- South Australia: Turquoise with brown band; white knickers; turquoise blue hose.

- Tasmania: Green, rose and primrose braces, map of Tasmania on breast with football in centre; white knickers; green hose.

- Victoria: Dark blue with white letter ‘V’ ; white hose; dark blue hose.

- Western Australia: Dark green jersey with gold swan on breast; white knickers; dark green hose with white tops.

Jubilee Finals: 29 Aug 1908

South Australia 16.20 (116) d Tasmania 7.7 (49)

Victoria 13.22 (100) d Western Australia 6.8 (44)

Because Tasmania was beaten by South Australia, Victoria was the only remaining undefeated team. Therefore, it was crowned the champions without the need for a Grand Final.